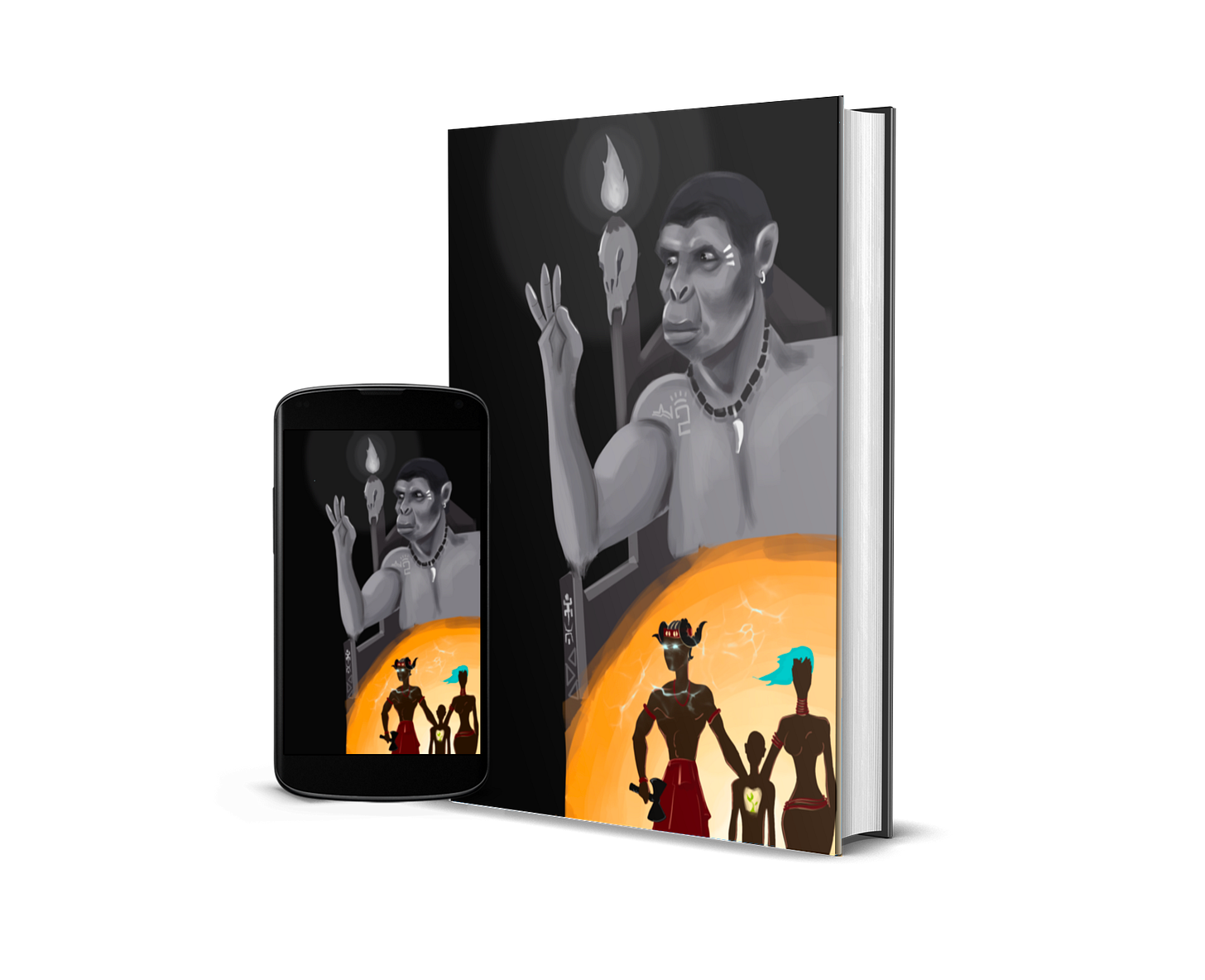

Words From The Great Ape Men – Artifact #4570

In the Beginning

In the beginning, they were three – the Great Trinity

Father, mother, and seed

The father, we called Amadioha

Knower of all things

Past, present, and future

The great mind of creation

And bearer of divine seed

The seed we call chi – divine energy

Know this, and join us

The mother, we called Eke Ala

The spirit womb of the universe

For no seed alone can grow

Without fertile soil to nurture

She is the bringer of motion, the birther of life

Know this, and join us

The divine seed, chi

Continues to live in us, through us, and with us

The soul that outlives the body

For energy can never die

But can only be transmuted

From one form, to another

From one life, to another

Know this, and join us

The fool sees lightning from the sky and calls it Amadioha’s wrath

They do not understand symbology

So they think Amadioha a mere being

A man in the sky

They see the python and call it Eke Ala

Observing the sacred rituals that forbid their killing

And other such rites they follow blindly to appear virtuous

They think they fool others

But really, they fool themselves

They speak of chi

Erecting shrines and offering sacrifice

Like the chi is of flesh that it needs to feast of goats

With eyes wide open, they still roam in darkness

Know this, and know you

‘Shhh.’

The man hissed and the boy was quiet. Between the croaks of toads in a swampy marsh, a twig could be heard snapping - or moving.

‘Can you smell it?’ the man asked his son.

The young boy sniffed at the cool air, turning his head left and then right.

‘You follow the sound, listen. Follow the breeze, sniff.’

Another twig snapped - moved. It was left of where they hid, leaning behind a large tree trunk with arrows nested in taunt strings.

‘It smells like anu ofia.’ the boy said.

‘Yes, it smells like bushmeat stew. It just needs to be cooked first.’ the man flashed a smile in the morning that still dawned.

The rainy season was making way for the dry now, leaving the swamp rising only a few inches past the ankles. It was not ideal for a hunt, even less so when stealth was a priority - but the boy had to learn. He had to learn to be able to do this at all times; in the rain, at night, and even in his dreams. After all, he was the first son of a d’nta – master hunter. And not just any d’nta, but an Ogbu’agu – leopard-killer. If the Ape Men’s adage that the snake must beget something long held any truth, then his destiny to become a master hunter was as much in his future as his own shadow was now by his side.

The animal’s head finally moved in the darkness as it stood on its forelegs as if to scan the area as a meerkat would.

‘Now!’ A shouted whisper.

The boy fired, hitting close enough in the direction of his aim, but too far to make a kill or injure his game. The arrow struck the ground near the creature and immediately, it moved to escape. First with a perked ear in the direction of the shot, and then a return to its four legs on the ground. The man released his arrow. A clean shot on target somewhere on the head. He had aimed for the eyes, but standing about twenty paces away under a sky still shy of light, any connection at all was a testament to his ability.

There was only a whimper, fast and low. And then a thud, as the creature hit the swamp.

‘When Ala holds the rain from us, this will not be possible. You will have to hit it on the first strike. Do you understand why?’

The boy shook his head. His father smiled, leaning out of the tree they had taken cover with.

‘The water holds the hunter, the water holds the hunted. We are gifted an extra breath of time to act as the prey digs its tiny legs out of the sunken sand.’

‘Just like we are doing now?’ the boy asked as they dragged their feet closer to their prize.

‘Yes, just like we are doing now.’

The bush was still mostly quiet, save the toads that wouldn’t stop croaking. Leopards did not roam so early or this far out of the forest, but snakes, one never quite knew. Both kept their ears open for the sound of a rattle.

The boy got to work retrieving the arrow. This part he had already mastered on one too many hunting trips. First, a little tug to loosen the exit, and then a hard yank twisting for ease to pull out. He dipped the tip in the water and then cleaned it with a rag no bigger than the size of his palm. Just before he gave it back, he dried what wetness was left on the weapon rubbing it over the cover cloth with a hard squeeze. This was a bronze-infused arrow tip, cast by the great hands of the Igbo-Ukwu uzu men; it was more for hunting than it was for battle because it was worth too much to be left in a body. Iron which wasn’t so difficult to cast was much better for war.

‘When will I be able to get my own bronze arrows.’ he asked his father.

‘You haven’t even crawled, yet, you speak of running.’

The boy said nothing.

‘When you kill a leopard with a spear or sword and earn the title of Ogbu’agu, you will be gifted with bronze weapons in honor of your bravery and skill, and you will then be welcome to the council of mighty men. For now, be grateful for the iron tips you have. Many fathers teach their sons only with wooden tips.’

Feeling somewhat defeated, the boy handed the arrow back to his father with a slouched shoulder. Pulling his iron tip out of the soft ground required no skill. He wiped it only because he needed it dry to protect it against rust and decay.

He proceeded to place the dead animal in their cane-woven basket after tying its legs together for easy bundling. When it was secure, he slung it over his back and tied on the carry strings to keep it steady. It was now time to head back home.

‘You should have seen me approaching my thirteenth rain, I barely slept most nights, waiting on the Ekpe society’s call from the elders of the fraternity. I waited so eagerly it’s felt like I was dreaming about it every night when I managed to sleep.’

‘But nna’m - my father, I am…’

The boy paused, afraid to admit that he was afraid. The rite of passage into manhood ordered by the Ekpe fraternity was a custom he could not avoid, unless of course, he wished not to be recognized as a man in Eke kingdom. Perhaps in his next life, he would come back as a woman. Then only his bleeding would be required for passage and no rites to keep him up at night would have to be observed. He weighed the words that climbed from his throat, and in what he could only interpret as shame, he gave into the choke of silence. This choke was slow though, so slow that it had allowed a first sound, a shrivelled whimper that cracked and died before it could ever become a whole word. It reminded the boy of the animal they had just killed.

‘It is okay to fear nwa’m - my child.’ he rubbed the boy’s tight curls as if to comfort him. ‘When you face the tests of manhood, you will find that it is as much a test of wisdom as it is a test of bravery. You have been born of my seed, channelled through the womb of a powerful woman blessed abundantly by Ala. There is more in you than you can see, but you must allow yourself to grow. How else do you think the sprout becomes a tree?’

‘You make it sound all so easy. I have been practising for how long now, and I can’t even hit this bushmeat on marshy ground, this one that is even slow to run. You must be ashamed of me.’

The father laughed a small laugh.

‘Anyi, you have trained since your tenth rain, and so have I. I have seen thirty-five rains since then, and you have seen just three. Yet, you look at my eyes with the arrow and you hope to see what I see, to know what I know.’

The boy sighed, perhaps his father was right and he had to resign from his haste.

‘A time will come when you will go back to your state before you ever picked up a bow. Your body will understand the hunt so well that even blinded, your ears will be enough. Even deaf, your mind will be enough. It is just like you cried through your first breaths and now you breathe without knowing.’

The boy’s eyes widened at the prospect.

‘How is that even possible!’

’Do you not eat pounded yam in the dark? Finding your bowl and then your mouth.’

‘Yes, but my mouth is on my head, a part of my body. The bow is not, nor is the prey.’

The man shook his head.

‘You are much too young for certain wisdom, but know it now that there is no separation between you, the bow, the arrow, the distance between you and the prey, or even the prey itself.’

The boy knew not to probe any further. Perhaps one day, these mysteries the elders were quick to speak of would be revealed to him too - how can there be distance yet no seperation. Maybe that was what it meant to become an elder, to have these strange truths revealed to you.

Soon, they were out of the marsh and on the dirt road. Other hunters were there too, most with bows and arrows, some with guns, the thundering weapon of the pig-skinned men.

‘Would you ever use a gun in hunting?’ The boy asked.

‘Perhaps when I am old and lazy with the white of my eyes leaking with milk. I only hope I never live to see the day these ones too will be called Ogbu’agu because they can shoot at a leopard and extract the teeth and claws.’ The man fingered the single tooth he wore as a pendant. They greeted the men they walked past, and the women too - carrying finish nets, farm tools, firewood, and water pots.

Eventually, they were back in the town. Walk paths worn from trampling cut the grey clay ground, bending around hut clustered compounds in different directions. Sometimes it was hard to know where one man’s obi stopped and where the other started. Other times, it was clear with short bamboo fences. In Eke, a man’s obi was his palace. There, he was king, ruling over his wives and children. Wives competed fiercely with ornamentation, painting the walls, and sculpting art. Children ran around and handled what chores they could be trusted with.

Now the darkness had almost completely given way to the light, a brightening blue sunless sky cast over the land. They could make out the hand-painted walls; geometric patterns the elders swore to be sacred, and symbols denoting many meanings - the tortoise for wisdom and cunning, the snake for intuition, the leopard for strength, the elephant for knowledge and truth. Each woman’s work had her style in it, but generally, they spoke the same language. A language the boy understood in the way that a boy could.

Greetings rang from the obis where people sat outside, some already gathering their uttaba herbal snuff for a morning sniff. A few held bamboo cups to hide their kai-kai drink, but most chomped on chewsticks and just went about their morning chores.

‘Ogbu’agu! Otutu oma.’ Leopard killer, good morning.

‘Onye nke chi ya folu efo. Amadi na edu gi dube’m.’

The man greeted them back, raising his bow to show his recognition. When the greeting came from his elders, he was quick to remind them that the prestige of his title held nothing in the face of the greying of their crowns.

‘I don’t understand the greeting, onye nke chi ya folu efo. Are there people that are alive in the morning, yet the morning does not rise in them.’

The man sighed. ‘You ask too many questions.’

‘Yes, and you said that the child that asks will become the man that knows, onye ajuju adahi efu uzo.’

‘You clearly inherited your mother’s head. But as for your question, I fear such sayings are not yet for you to know. These are the things you will come to learn in your years of Ekpe. Perhaps I can tell you why it is called Ekpe.’

They made way for a goat herder driving his livestock into the pen, and then avoided a palm wine tapper with his climbing ropes and tapping pot.

‘Is it called Ekpe because it is the python-speak for left hand, aka ekpe.’

‘Congratulations, you know what the word translates to, but do you know what it means?’

The boy was silent.

‘These pig men and their ways are eroding our language. You know, I hear that in some territories where they have dominated, our children no longer know how to read akala left by the first men on the rocks of their own sacred grounds. They can now only read pig men symbols. Alphabet is what they call it. They spell our own words in this alphabet. I even hear rumors that some of these rocks have been destroyed, sacred trees cut down.’ he spat on the ground in disapproval, ‘alu!’

The boy was not sure why these things were important. Language, inscriptions on stone left by the first men - the great ancestors, sacred trees, and other such things his father cared so much about. Were languages not just words? Were rocks and trees not just things?

‘It is called Ekpe, or as you say, left hand, because since you were a baby, you have been practicing with your right hand, your natural hand. The ancestors believe that from your seventh rain until your thirteenth rain, your mind grows to learn left from right – good from evil some may say, though it is much deeper than that. This is why it is our way that when you come of age, a basic rite is required.’

‘A basic rite? There is more?’

‘If you choose or are chosen later, you may come back to be put through the master rites of the left hand. You will be taught how to use both hands with none ruling as master over the other. It is only after then that you may become a human being, a full human being - nmadu.’

The boy squinted as if to process the newfound information with his eyes.

‘But then, why don’t they just make us sculpt wood, clay and stone with our left hand? Surely, that must be better than whatever it is that happens in the bush they take us to.’

The man smiled.

‘You see my son, when the Ekpe speak of the left hand, we do not speak of the hand at all.’

‘Hmmm,’ the boy stopped at the front of their obi.

‘Then what do we speak of?’

The man placed his bow down and then unfasten his sword from the sheath that held it on his waist. Now wearing only his goatskin skirt, he felt much lighter.

‘We speak of the mind, the right mind and the left mind. We speak of the clear soul, the unified clear mind. We speak of mnuo, auras - and of chi, energy.’

Nnanyi

An ogbuagu (wildcat killer). He wears his badge of office on this neck (the canine for his feat as a hunter). His sheild is made of hardened skin and animal shells, his spear is casted from bronze. He is the father of Anyi and a well-respected man in the kingdom from the respected class of diala.

Ogbuagu

Ogbu + agu = Killer + Leopard = Wildcat Killer

An ogbuagu is considered not just a good hunter, but also a brave warrior. It is one of the most respected titles in Eke Kingdom and it can only be earned and not passed on from father to son.

THANK YOU FOR READING

I found myself narrating this in my head and it was very nice! I like this series.