Anyi’s breath found calm in the voice that called his name. Even in a dream, he could recognize it with ease.

’Nnanyi? What is happening?’

He moved himself away, conscious now that it was his own father he had attacked. He still panted, his small chest rising like tides only to crash and rise again.

‘You have done well.’ His father was now on his feet, looking down on him with a masked face.

‘Is this it? I passed the Ekpe test?’

There was a growling at the door and in came the panther from before. It took slow powerful strides to Nnanyi, and he touched it on the head. First a tap, and then a rub. The growling died fast, but Anyi still struggled with breathing freely.

Breathe, breathe.

There was movement from the corner of his eyes and he turned to focus. The night couldn’t possibly get stranger, but it did. Two masquerades he had thought to be stuffed figures like scarecrows moved out of their place and closer to him and his father.

‘This is only the first stage, and in many ways, it is as much about you as it is about me. Imagine my shame if you could not muster the courage to fight back?’

’So, I don’t understand?’ Anyi kept his eyes on the two figures, ‘were they here to watch us?’

‘Well, they say the lion only seen with two eyes could have been a goat. I may not be your examiner and your accessor.’

Anyi’s breath was finally back to what he remembered as normal.

‘So why didn’t one of them fight me instead?’

‘Each man knows his son. Another fighter might be too hard or too soft. And there is the matter of accidents. Ekpe Society would rather a man slay his own son than see him die in the hands of a stranger.’

Anyi’s face twisted in the dark, unsure of how he felt about the last statement.

‘So this is it?’ he asked, ‘I’ve passed? Courage is the substance of manhood?’

The figures had reached them now.

‘No my son, courage is only the beginning.’

Anyi felt a hand on his face, the taste of bitter on his tongue and the smell of something pungent in his nose, his eyes stung too. He blinked and he blinked some more, but the room would not hold steady as his father’s masked face appeared to double and then triple.

‘Courage is only the beginning.’

It was the last thing he remembered hearing.

When Anyi woke up, it was in a large hut with at least thirty other boys by his estimation. There was no mat to rest on, only clay - there was barely space too. Mangled almost like lifeless bodies, the room was a river of flesh with barely any space for a footing. Anyi rubbed his nose and adjusted to the light. Without the cocks that crowed, it was hard to tell the time in the absence of light.

Courage is only the beginning.

These words echoed back to him in the voice of his father, but in place of Nnanyi’s face, there was only the black of a mask staring at him with white eyes and scary teeth. Now that he felt like he was waking from a slumber, he wondered if it had all been a dream. Had he, Anyi Isieke, fought a panther and bared his teeth? And what about his home... How did he get to the forest in the first place?

A body next to him shifted and the boy began to wake. Anyi wondered if there were others awake that feigned sleep. He remembered Ozi and how she sometimes pretended to be asleep so she could be carried to her bed. He also remembered the bush meat known to play dead with the eagles squaked. He too was awake, but did not move very much. He wondered if Tobe and Uzo had made it this far.

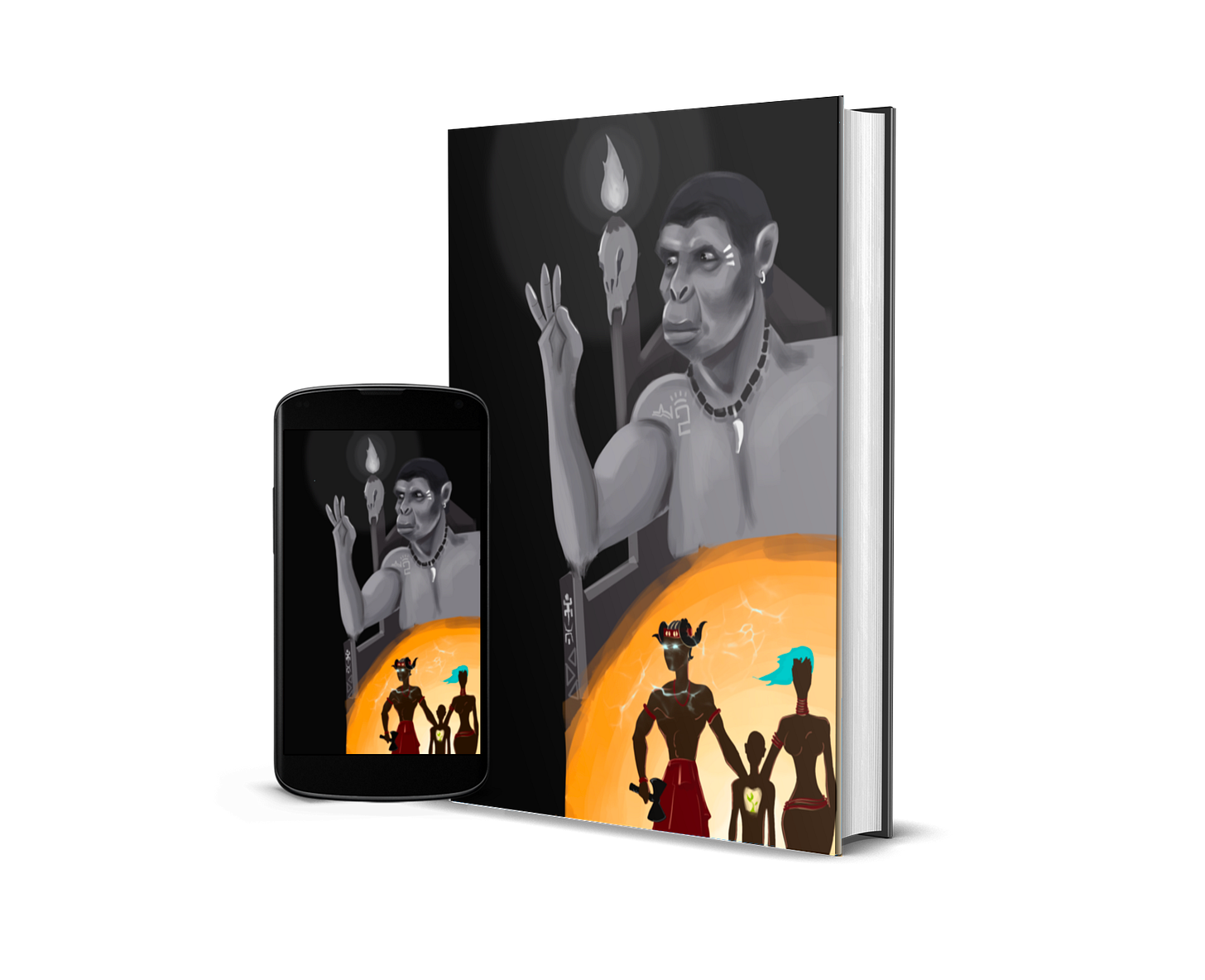

From the round open windows, the sound of Ekwe drums swam into the room, and on command, the boys began to rise. Most knew little of the Ekwe drum rituals, but for the Ekwe, even little was enough. There was no spirit more revered than that of Ekwensu, the spirit of war, conquest, and domination. Not just of enemies, but also of the earth in general - plants, animals, the rivers and land. Ekwensu was not a spirit to dwell in for long as many believed Ala which spoke more of living with the land and not dominating it was a stronger philosophy. But eventually, when war called, as it sometimes did, Ekwensu was the spirit to summon, and there was no louder call than through the Ekwe drum - a double-slitted hollow wooden drum in the shape of a cylinder.

As the boys wiped the tiredness from their faces, the chime of a masquerade’s bells could be heard. They already knew what followed, and before it, they already panicked. Through the window, different masquerades climbed in, each wielding a cane in hand, and the will to use it too. Over the sounds of the ekwe drum, they flogged the boys without mercy and the boys fell over themselves trying to force their bodies through a single doorway. There was shoving, pushing, and trampling too. But not a lot of escaping as everyone fought to squeeze out of the same door. If they didn’t settle into the panic, and all tried to get out before the other, there was to be no progress.

'We need to calm down, we need to calm down. The strokes can't break us.'

Anyi's voice was lost in the crowd, but he called out again and again until someone echoed him. Soon enough, the message rang clear, making its way to all ears in the room. The boys adjusted to the flogging telling their bodies to be prepared for the pain. The chaos turned to order, and slowly, the hut began to thin. When this thinking as one seemed to have covered the room, the masquerades stopped and fled from the windows they had come through. Anyi wondered if his father was one of them. And he wondered yet again if he had been dreaming, if he was still dreaming.

The boys spilled out of the hut, until Anyi was through. The compound was large and mostly bare save palm frond broomsticks that littered the ground and three masked men; one beating an ekwe drum. The boys paused, not sure if they were still playing a sort of game. It made no sense having broomsticks over sand, were they to sweep the field away?

War will call, when war calls

For steel, for sweat

For men, and more

War will call, when war calls

The strong and the weak

Who is strong? Who is weak?

War will call, when war calls

For me, and you

My war is yours, and yours is mine

War will call

War will call

Who is me? And who are you?

Who is we? Who are we?

The drummer stopped, abruptly ending the poem he had been chanting.

‘You are now at war!’ One of the masked men barked. He moved his large bulk closer, his gorilla-like frame inspiring fear with the mere heaving of his naked chalked chest.

’Aziza.’ He held out the broom he was holding. There must have been at least two or three hundred dried fronds in the bunch. He held it in both his hands, and in a display of monstrous strength, he snapped it in half with bulging veins like vines tracking a tree trunk. The entire bulk did not snap all at once, not even a real gorilla would have managed that. But one after the other, he managed to bend it and then break them all.

The other masked man walked up to the boys and handed a broomstick.

‘When you have done as we have done, you will win the war.’

The boys looked on in bewilderment. They hoped for more information. Perhaps clarifications regarding instructions, rules, anything. The masked men were done and the drummer was at it again. He played and chanted until the masked men were back to him, then they helped him carry the large ceremonial ekwe, one man at each end of the cylindrical instrument. There was no talk about how long they had, if they were allowed breaks or should expect nourishment after some time. From the looks of it, there wasn’t even a well of water to draw from. If the afternoon heat found them here, some might not even make it.

‘Let me try it.’ It was Tobe and his loud voice. He was a big boy, taller than most, wider than most, stronger than most. The boy that had received it was happy to pass on the burden. Tobe held the broom in his hands as if to weigh it in his mind, and then he gripped it hard to bend. And sure, it bent. Bending the broom was easy, even the scrawniest of the bunch could manage that. Breaking it on the other hand was something else. Together, pulling strength from his back and arms, he tried. Not even one of the fronds was snapped. Tobe stopped to draw breath, and then he tried again, the side of his face pulsing as he clenched. Still, nothing. Just a strained palm and tired muscles. Anyi’s eyes searched for Uzo but he did not find him. Perhaps he missed him, perhaps he did not make it past the first stage.

‘Let me try.’ Another boy offered. He was shorter than Tobe, but he was stalkier, with muscular arms he had clearly inherited from a parent or both. Tobe tried a few more times, mainly to douse what Anyi imagined would be shame, needless shame. The kind that came only from the slaying of pride. It would not be enough to snap the palm frond broomstick.

The new boy tried, and tried again until he was tired and begged for a volunteer. Others joined, bending, twisting, twisting and bending. Nothing worked. When the sun was in the sky, not even a single frond had been broken, but many spirits had been crushed. The initial enthusiasm was now down to a solemn congregation hoping for a miracle.

The boys continued trying as they could, hoping that over time, their collective efforts would have weakened the broom and a crack would appear. The morning gentle sun gave way for the scorching of the afternoon blaze and still, progress was at best a mirage that looked like hope. At this point, Anyi and some other boys decided to make their way back into the hut. At least there the shade would delay the onset of what now felt like a brewing delirium.

‘Are you just going to give up.’ A boy had asked.

‘I don’t know what we are supposed to do, but none of us here can break that broom.’

’So we are to wait till they find us resting? Perhaps they want us to persist.’

Anyi thought about it. The test from before had been about persistence in a sense, more so courage, but it was on the same path.

‘I will be out soon, we will be out soon. Perhaps we can take turns resting. Everyone breaking in the sun won’t make us any stronger.’ Anyi left the boy and went inside. He was surprised to find Tobe seated, his back to the mud wall.

‘My father is going to be so disappointed.’ Tobe said.

‘All our fathers are going to be disappointed.’ Anyi replied.

‘Courage is only the beginning. That was the last thing he said to me.’ Tobe looked at his tired hands, ‘how is courage supposed to help us break this broom!’ As Anyi and Tobe talked about the previous task, more boys joined them in the hut to rest and each added to the tale of manhood.

Some never ran and never met panthers, leopards or lions. Others like Anyi did and had to get their courage coaxed from where it was buried. Tobe was one of the few that never ran. As it appeared, his courage or brute strength counted for little in this test. Perhaps it was about endurance. But had they not already endured enough?

‘I can just see his face when I tell him that we failed.’ Tobe circled back to his underlying fear, ‘you know, when one of us breaks anything in the house or misses their task, my father punishes everybody. He says that one person’s war is all our war. Just like in the chant.’

‘A nalu ofu onye azu, a nalu go aro azu.’ Anyi echoed.

It was a popular saying, as old as the Ape Men. It translated that when fish was taken from one man in the tribe, it was the whole tribe that the fish had been taken from.

‘One time, we all had to put hands together to clean the huts because my big sister had forgotten. It was the first time I ever touched a broom, I wasn’t even old enough to sweep back then, but I got a share even if it was only the small bath hut.’ Anyi listened to Tobe’s story, not sure who it was meant for.

A boy appeared in the doorframe holding the broom.

’Tobe? You don’t want to try again?’

‘Bring it, bring it!’ Anyi shouted and sprung to his feet. ‘Ike aziza bu na nchi kota - the strength of the broom is in the gathering.’

The boy at the door did not understand what Anyi was getting at, but he handed the broom to him without protest. Anyi wasted no time unfastening the rope catch that held the fronds together, and then he began to hand the fronds to each boy, no more than ten fronds each.

They felt stupid not to have thought of it much earlier. If one person’s war was the war of all, then surely, the burden was for all to share. Just like the wild cats had helped some to find their courage, the flogging out of the hut was to help them settle into thinking as a team.

Ten sticks at a time, the palm fronds snapped with ease and the task was over with. When they were done, they slammed on the goat skin drum in their hut and the masked men reemerged from the bushes they had disappeared into. With them, there was a wooden contraption wheeling a large three-legged pot and the forbidden ero mmuo - spirit mushrooms.

The Ekpe graduation ritual did not take place till the moon was high in the night. The boys had still not been fed. They were congratulated as a group on completing the task but none of the instructing masked men bothered to ask who had figured out the trick to split the fronds. When some boys tried to make Anyi a hero, they were cautioned against it. Failure would have been shared by all, so glory could not be taken by one.

When the time was right, all the boys were asked to go outside. One by one, they were to come in for the final test. A confrontation with the spirit. It was believed that the spirit mushroom was a sort of portal that allowed one to transcend without death or even the powers of a d’abia. Upon ingesting it, each was to be confronted with something about themselves. No one knew what the next saw, and it was forbidden to ever ask or speak on it.

One by one, the boys went into the hut. Coming in through the door in the front and leaving through the window to the back. Anyi waited, his ears sweating with the nerves that also swirled his stomach. Eventually, it was his turn. He walked into the hut to find a small oil torch burning, two men sat on a mat, a bowl of steaming liquid with mushrooms and the bark of a tree floating.

They spoke in a language he did not know, and they marked his body with nzu chalk, dots and patterns.

‘You will go, and you will return. You are of here, and you are of there.’

He was given a calabash to drink from and he took no more than two bitter gulps, swallowing some mushrooms while at it. The last thing he recalled was a fever, a burning in his eyes, the blurring of his vision, and finally, darkness.

First, there was blackness, and then came the roar of a sound he did not recognise - a strange roaring rattle. His eyes open to find himself suspended in the air, both hands gripping a metal contraption of some sort. Without thinking, he pulled on the bars he held and his arm jolted and shook as sparks flew from the equipment. Perhaps this was some type of gun. One that did not spit single bullets like the rifles he knew, but hundreds. Bronze-coloured cases fell as he fired, and a belt by his feet moved into the chamber.

Anyi gathered that he was trapped in another body, one caged in a sort of metal bird flown by two pig-men. By his side, another pig-man was there, eyes blue as ice, feeding the ammunition into the chamber.

Breathe, breathe.

He heard it in his head, wondering if it was the body he was in that spoke it, or if it was him, or if there was any difference at all. For one thing, this body he was now in was larger than he recalled himself to be. He could tell from the distance to his feet to the ground that he was a man now. The hands he could see were dark, like the tone of his skin. What was an ape-man like him doing with a pig-men? Flying in a technical contraption, agbara ekwensu. The words flashed in his mind, science and nature dominating spirit.

Breathe, breathe.

He caught the body he was strapped in controlling its breath, focusing the scope on the gun it operated. Again, he pulled, bullets flying and wreaking havoc to another mechanical contraption he did not recognise. A sort of iron machine that moved, a barrel mounted atop of it.

He lost his footing and staggered, but there would be no recovery from this. The mechanical bird spun out of control in a spiralling motion that headed down. Without thinking, he jumped. And then he pulled a strap on his uniform. It was not like the pig-men uniform he knew, not exactly, but it was more like it than anything he had seen in Eke. He even noticed badges on his chest and shoulders. What did these badges mean and why did he have them on?

He felt a tug and then lightness as what he thought of as a huge wrapper cloth exploded out of his back. Slowly, he glided through what he was now sure to be a battlefield. The crackling of guns like he had never heard climbed on top of each other, and screaming and grunts followed fast. When he was low enough to the ground, he found a blade from his waist and cut through the strings that held the giant wrapper cloth that allowed him to float.

He moved without thinking or willing, and even when he willed himself to stop, he continued to move. Crouched to avoid getting shot at, he found a trench where men dressed in what he now recognised to be Anglon uniforms waited. He peeked above to take a look at the enemy. A bullet burrowing so close it caused sand to rise and hit his face forced him back down. He reached for his shoulder and retrieved a gun. Much like the rifles he had known, but with much more going on. His hands moved, pulling and clicking parts to ready the weapon.

When he was done, he raised his rifle to take aim. The men running towards them were pig-men. Pig-men killing pig-men. This was not his war. A bullet connected with the man next to him and blood splattered everywhere. He took out a few soldiers running to flank them and then he settled down in the trenches to reload his weapon. First, he discarded the empty cartridge, and then he withdrew another to slide it. Before he did, he paused to stare at the shinny bullet at the top. In it, a case stared back at him, strangely familiar, yet different. He froze in horror, and then he woke up with a cough.

The last thing he remembered was the bullet on the cartridge and the face on it - an older version of his face with bright blue eyes staring back at him.

‘It cannot be. It cannot be.’

‘Shhh, the spirits have shown you what you need to know. Now leave through the window. And know that the day what you have seen leaves your tongue and meets an ear, you will surely die. You, and your destiny with you.’

‘But,’ Anyi wanted to protest.

The men were silent. A warning silence that told him the test was not over until he left, and would never be over until he was dead. Being a man after all, was not the function of a single rite. It was a lifetime - of courage, comradery, and whatever this was.

Silently, Anyi escaped through the window, a strange dread that blue eyes haunted him prickling at the nape of his neck.

Commander Stone’s Interlude

Dearest General,

I hope this letter finds you well sir, and that Anglon is making great strides in establishing her colonies in other regions beyond the Ogbi. I am writing to report what I have seen here, with my own two eyes, and what I have learned from the priests, and the few locals I have brought into our fold. This place, this Ogbi land, is like no place my eyes have ever been. In fact, dare I say it, there might be no place like it at all in all of the known and new world.

I will start with the basics, power and government. I mean, it is what we are here for, isn’t it? To overthrow the power and to claim the government. If we do not do this, how can we hope to civilize them in the ways of Anglo through faith in Xrist.

The Ogbi’s do not know kings, not as other tribes do anyways. They run a decentralised government with regional rulers they refer to as Ezes or Obis. These noble rulers can be in rare cases built on paternal lineage, but mostly, they are selected by a council and can only rule for seven years. Their sons if they wish to be rulers must then earn their own place. It is the case with their highest offices as it is the case with their chiefs and councilmen widely known as ndichie - titled men. There is a story told among the locals of a king who got taken to the forest and tied to a tree until he died. His crime, claiming the land for himself and trying to lord when he was to serve. In Ogbiland, it is forbidden to kill a king, but apparently, not to let him die. As you can see already, they are a technocratic race - they will not be easy to break. It doesn’t help that even outside of the kings, if I may call them that, there are groups like the order of first daughters they call the Umu Ada in charge of women affairs. Power if very decentralized.

On the military front, they have developed many armies scattered around their lands, but they aren’t standing armies as they do not see war as often or as bloody as we do. If they were ever to unite as one, even without the other tribes, they would be too much to bear. As it is now, they are weak from divisions that stretch into the slave era. Our supplies of arms have done well to fuel the conflicts that exist. We must not relent. At least their weapons are still no match for the Maxim Gun, but we must take their ability to plan and their advantage of the terrain very seriously. We do not want a repeat of what happened with the Oba in Idoland. If we are to take this land, I do not doubt that bloodshed is a price that must be paid. From all accounts, they are not the kind of people to go quietly - pride is strong in them, knowledge is too.

The soul of the average Ogbi is at home in who they are and to know it, you must first understand their language - it is the root of their very culture. My learning of the language continues to prove difficult, the curved mouthfuls they speak are often too heavy for my Anglon tongue, but I know enough to know that it is very different from ours. The Ogbis for example find it offensive when a word is introduced into their language from a foreign language. Not like Anglon with root words in Latine or Griik. If we do not take this language and its meaning from them, we will never be able to break them.

For religion, like everywhere else, understanding is on a spectrum. I have met with the wiser of them, and they have demonstrated a sophistication in philosophy breaking down what we call their gods into concepts that map the internal human environment. I have also met the less esoteric, they worship in a manner you may think of as idolatry - making gods of their symbols and even offering animal sacrifices like Abrahem of the Old Law in the Xristian tradition. Just like we can tell esoteric Anglons from the blue of the eyes compared to the grey-eyed blind followers, you can tell the esoteric Ogbis from the brownness of their eyes. No grey-eyed Ogbi can ever dream of becoming a titled man. They even have orders of cults one must pass through to gain knowledge of their own enlightenment before the opportunity of such roles even arise.

As a people, they are civil, mostly welcoming, and prone to artistic impulses like dance, poetry, and theatre. Their oldest writings appear phonographic compared to the current iconographic system in use. Fortunately, there is no paper technology, so their history should not be very hard to erase. I have attached in this letter a map of their land, and notes on what we will need for military action should it come to that as I fear that it will. After all, a people hard to rule even by one of their own will not easily bend to the will of another, an outsider.

They are yet to discover the power of light energy crystals and sometimes regard guns as dirty. But they have mastered many things, like the art of metal bending, agriculture, textile, and the likes. It is their belief that technology is separate from civility. The wise among them think us mentally advanced but spiritually blind. These ones must be the first to go.

God bless the Queen, and long lived the Anglon Empire.

Yours truly.

Commander James Stones

P.S - Of all the Ogbis, we must be most vigilant with the Eke region. If not for anything, they are the kind to look one in the eye and never blink. They are snake whisperers, and a people of great ancestral veneration - their memory is long and their priests wise.

The General read the letter, once, and then again and again; brows furrowed and nose crinkling in certain parts. When he was done, he folded the paper gently and then he found a file for it, adding it to a stack of many. He placed his hand on a black contraption on the large oak table, and then he dialed the knobs on it until it made a crackling sound.

'Reverend Snow here.' a voice called from the contraption.

'Deploy protocol Canna. What is brown must first go grey.'

'Understood General Sax, consider it done.'

The contraption crackled again, orange light emanating from corners of the black box not sealed tightly enough.

Commander Stone

A colonial soldier invested in the project of taking over the Ogbi lands. He is loyal to the Anglon Empire and his ranking General. He is a strategist at heart and has a knack for writing letters. He is of the Hobbesian view that colonization is natural and unavoidable process resulting from the human impulse towards desires that go beyond subsistence. He fancies the value of his home civilization higher and considers his race the Prometheus to the tribesmen of Afaraka.

THANK YOU FOR READING